The prolonged Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant rise in the number of depressed patients has reignited the controversy over the prescription rights of antidepressant drugs based on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

A recent OECD report placed Korea first among 37 member nations in the prevalence rate of depression and at the bottom in its treatment rate.

Against this backdrop, various medical associations, including the Korean Neurological Association (KNA), stress the need for the government to abolish restrictions on the prescription rights of SSRIs by non-psychiatric physicians.

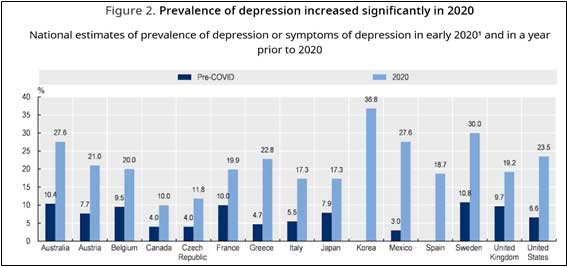

“Since the start of the Covid-19 outbreak, the incidence of depression in the world has more than doubled, and the prevalence rate of depression in Korea was the highest among the group of industrial countries, with 36.8 percent,” the association said. “It is shocking that four out of 10 Koreans feel depressed.”

Nevertheless, Korea is the most difficult country globally to receive treatment for depression, it added.

According to the KNA, the low treatment rate is due to the regulation, which restricts non-psychiatry doctors from prescribing SSRI-based antidepressant drugs for more than 60 days, introduced in March 2002.

“The regulation banned non-psychologists, which account for 96 percent of all doctors, from prescribing antidepressants,” the association said. “The 60-day prescription limit for antidepressants is a bad regulation with no scientific or medical grounds.”

Because of this regulation, the accessibility to receive treatment plunged from 100 percent to 4 percent, placing Korea at the rock bottom in the depression treatment rate, it added.

Citing a survey of 36 countries worldwide, the association stressed that no countries restrict non-psychologists SSRI prescriptions.

“In the U.S., even nurses are prescribing SSRI antidepressants,” the KNA said. “The government should immediately abolish the restrictions on the prescription of SSRI antidepressants so that 100,000 doctors in Korea can treat mental problems preemptively, it added.

In January, the Korean Academy of Family Medicine (KAFM) also emphasized the need to abolish the regulation restricting non-psychiatry doctors from prescribing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant drugs.

The KAFM noted that by lifting the restriction on non-psychiatric doctors from prescribing SSRI antidepressants for more than 60-days, family medicine physicians would be able to manage depression effectively.

“Korea is the only country in the world that is limiting a treatment that all doctors around the world safely use as a first-line treatment for depression,” the association said. “To lower the suicide rate in Korea, all doctors in family medicine departments must be able to diagnose and treat depression early.”

However, the psychiatrists’ association remained adamant that the government should maintain the current system to prevent misuse.

“Neurology is a medical department specializing in the sense while psychiatry is a medical department specializing in emotions, thoughts, and unconsciousness,” an official from the Association of Neuro-Psychiatric Practitioners told Korea Biomedical Review. “The restriction on SSRI prescription is based on such different treatment areas.”

The official stressed that there is no need to remove the SSRI prescription restrictions as Korea has excellent medical access, and it is easy to meet specialists in mental health medicine.

“More urgent is a system that quickly links people with depression who visit other departments to mental specialists,” he added.

However, the psychiatrist group’s assertion does not apply to the rest of the country, as many provincial areas have low access to psychiatric care.

Out of 229 cities, counties, and districts across the country, 37 had no mental medical facilities as of the end of 2019. There were no mental disease facilities in 10 out of 18 cities and districts in Gangwon Province and eight out of 23 cities and counties in North Gyeongsang Province.

Despite the continued conflict between psychiatrists on the one side and neurologists and other physicians on the other, the issue is at a standstill as the decision-makers, such as the Ministry of Health and Welfare, have consistently taken a passive attitude toward the problem.

“As long as different medical societies make conflicting claims on the matter, the ministry cannot forcibly change the regulation,” a ministry official said. “The medical associations and societies need to come up with a compromise.”