Rijan Slater, Business unit Director of Janssen, analyses on how to treat mental illnesses in Korea

The Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson has been treating and preventing some of the most complex diseases of our time since 1961.

Later in 1983, Janssen Korea ltd. was established in Yongsan, Seoul where Rijan Slater, the Business Unit Director for Neuroscience Business, would explain to me the report about Mental Health throughout Asia-Pacific countries. Janssen had funded UK-based economic research institution the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) to initiate the research to produce “The Asia-Pacific Mental Health Integration Index”.

He also enlightened me about the Gangnam Murder case back in 2016 against the stigma of schizophrenia and other mental diseases. On May 17th, 2016, a 34-year-old man stabbed to death a woman he had never met before, and later claimed that he did so out of his hatred for women as they had ignored and humiliated him all his life. The police later refuted his claims and said the incident was not a hate crime against women, as claimed, but one driven by mental illness.

The doors with Johnson & Johnson etched in with pride opened and my eyes adjusted to the towering figure in front of me. Cranking my neck just to look up into his eyes, I blurted out a question he must have heard hundred times; “How tall are you?!” With relief he took it with humor and chuckled before stating he was over 190cm. He bended his body with ease onto a chair and gestured me to do so as well.

Please introduce yourself

I grew up in England with my career before moving to Australia in 2011 and in 2013 I moved to South Korea. My job is to understand our markets better and looking ways in which we provide services and products to patients. One of the reasons why I came to Korea was that during my time working in Janssen Australia, we have close connections with Asia-Pacific so I experienced meeting my Asia- Pacific colleagues a lot and I got to know many people within Asia. One of the things that I was keen to do was to get an opportunity to do some things that were different and get diverse working experience. I talked with my boss about an available job in Asia and a job in Korea popped up. My wife, my son and I decided to go for it and we really enjoy our time here.

Can you briefly explain this report you are currently analyzing called “Mental Health and Integration supporting people with mental illness: comparing 15 Asian pacific countries?” and why are you interested in this?

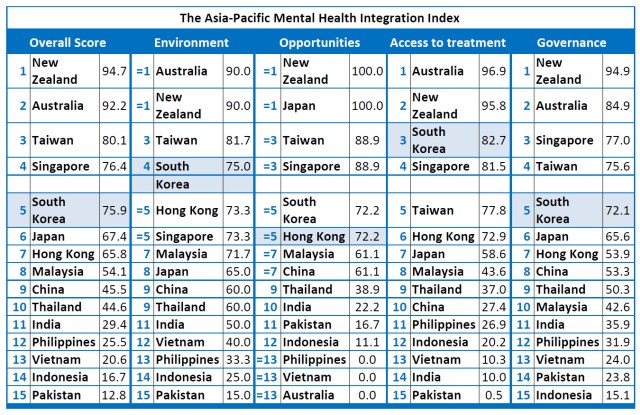

If you look at what the report is about, it’s comparing 15 Asia-Pacific countries and looking at their level of commitment around managing and integrating patients who live with mental health issues. What’s interesting is that it shows a vast and stark difference between higher income countries such as Australia and lower income countries. There is a distinct need for more to be done to support patients living with mental health in all aspects. The key categories that were outlined was the environment, access to services and medications, opportunities to patients for example job findings as a way to integrate them more into society and also government funding. It surprised me in some aspects because if you look at Korean health system that is ranked 75.9 in the index, it is often seen as the forefront of the leadership in Asia but it’s behind Taiwan (80.1) and Singapore (76.4). You would’ve expected that Korea would be ahead.

In your opinion, why do you think South Korea is ranked 5th among the 15 Asia-Pacific countries?

One of the biggest differences you will see with the mental healthcare centers in Korea is that it’s very hospital-based. Having treatments and seeing your doctor means spending a lot of your time as an in-patient in the hospital. If you compare this in different countries where they have more community mental-health setting, you can see the vast changes around the time and amount of in-patient hospitalization. In Australia, 85% of patients are managed within the community mental-health setting whereas I can say that is probably switched the other way around in Korea. The other key is investments; if you look through the report and see healthcare spend for mental health in Korea, only 2.6% of the healthcare system spends is devoted to mental health, where it should be 5%. They recommend this number because the financial burden of mental health is huge on the economy so larger investments upfront will create longer-term reduction in managing mental health.

Can you explain how the countries in Asia-Pacific have different approaches for patients with mental illness?

If you look at the top to bottom, the distance between those is immense. The bottom is the poorer Asian countries where if you live with a disease like schizophrenia, you are locked up in rooms or wards. The treatment of patients in these countries can be awful whereas Australia and New Zealand, which are at the top, there is a lot more emphasis on how to manage patients and to lead them into a normal life. Can you integrate them back into society? To be like everyone else where they can have jobs, relationships and buy houses? They ask themselves these questions. One thing that is consistently stuck whether you’re looking at the top or bottom country is the stigma that surrounds living with mental health. Even in a country like Australia, there are still huge amounts of stigma to patients who would not want to admit that they have schizophrenia, or not tell their employer they have bi-polar disorder and other similar diseases. There is exclusion linked with mental health and it works in different ways in different levels where one example is chaining someone up in a poorer Asian country or exclusion can be from work or from social settings in Australia and New Zealand.

What ideas do you have about policies, programs and services available to help patients with mental illness in Korea?

We have many meetings about this topic and what I really love about working in Janssen Korea is that we really do put the patience and focus on what we are doing. It’s not just about selling products; it’s also about how we set up services, care pathways and support networks so patients living with diseases can live happier, healthier, more longer lives. As I said, I highly suggested the community mental-health setting so what I’m focusing now is how we can get that on the agenda and how we can engage with the Korean government on providing these services and how we can stop excluding them from society. This is the biggest subject we are targeting on as a company right now. We know that the evidence strongly suggests moving patients into the community-care model where they can have access to psychiatrists, a multidisciplinary team including case managers, social workers, medication, psychosocial interventions and family-psycho educations. With these, the outcome of the patients will get better. What is also essential is the medicate policy around treatment for mental diseases. The medication policy actually inhibits the ability for patients to get access to medication; this means that in the drug market, there are products which clearly show on having great impacts on the outcomes for patients but unfortunately, unless they have strong financial backing behind them, patients would not have access to these products.

We have the responsibility to persuade the government to give patients the funding. The last area we would like to focus on is multiple relapse in Korea. One of the biggest causes of multiple relapse overtime is through poor adherence to medication. With schizophrenia, every time you have a relapse you lose some of your brain functioning that you never get back. These patients would lose more brain function to the point where they are unable to engage in normal life. One example I would like to suggest in order to treat this would be replicating Spain where they have long-actable injecting treatment to which patients would have one injection per month or every 3 months. From this, they are not relying on everyday pills which are a daily reminding of living with a disease. Looking at these countries that have this treatment have really good outcomes.

In your perspective, do you think there is a stigma against people with mental illness in South Korea, despite the continued efforts to improve mental health policy? What kind of stigma? Can we improve this?

I can’t think of any country in the world where there is no stigma involved; a lot of which stems from how the media reports mental illnesses. At times, it can be often sensationalizing the disease as a reason why something happened. What happened in Korea shortly after I first arrived was that a poor lady was murdered in Gangnam Station. The news talked about the murderer’s relationship with women but it turned out he has previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Hearing that link between schizophrenia and a murder causes a big impact on society and the media can take advantage of the situation to cause fear. It’s embedded into all societies, not just Korea. The stigma can also be caused by the health care system: say for instance you are a relatively high-functioning patient living with schizophrenia, able to have a job and lead a normal life but you are moving towards relapse. This means having to go to the hospital and staying there to control your disease, as an employee you have to leave the workplace and stay in the hospital for long periods of time. Maybe if you have a community-based mental health system, you can quickly get the symptoms in check. So the health care system can be partly responsible by excluding people from jobs and education. But what depends on it all is the fear behind people who have mental health issues and listening to worst case stories who are heavily publicized.