If delivering a baby is never easy even for girls in their prime, it should be far more so for working women in their late 30s and 40s.

“I had my first child at 38, and natural birth wasn’t a viable method for me because I previously had uterine surgery. I also worked for most of my life and did not plan for children until much later,” said Lee Soo-Yeon, a working mother in her 40s, who had a planned caesarean section.

Choi Jung-hee, a mother, working as an elementary school teacher in her late 30s, tells a similar story. “I was planning to have a vaginal delivery, but when I went into labor six years ago, the baby’s heart beat kept going down to zero, and each contraction was suffocating the child. My doctor switched me over to the C-section.”

Caesarean section, a term that originates from Julius Caesar who is alleged to have been born through such a method, is the surgical method of delivering babies when a vaginal delivery would put the baby or mother at risk. The mother is first put under anesthesia, upon which a doctor cuts around 15cm around the mother’s lower abdomen to open the uterus with a second incision to deliver the baby. Doctors then stitch the incisions after delivery.

Although C-sections are potentially life-saving and sometimes necessary, doctors do not advocate the practice due to possible complications that may arise during and after childbirth. The international healthcare community considers the ideal rate for Caesarean sections to be between 10 to 15 percent of total childbirth.

However, the popularity of C-sections has been rising all over the world, with experts in China and Vietnam calling it a “cesarean epidemic.” The Dominican Republic came in first with 56.4 percent, followed by China (47 percent), Mexico (45.2 percent) and the United States (32.2 percent).

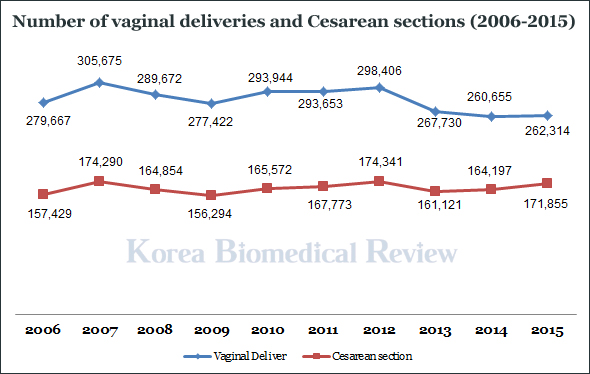

Korea has the 12th-highest C-section rate with 36.6 percent of all births performed this way. Despite national efforts to curb the rising number of C-sections, statistics have shown the steady rise of the surgical method.

C-sections are also the most performed surgery for those in their 20s and 30s, the age bracket where most women in modern society are driven to work long hours in Korea’s competitive society.

In contrast, some European countries, such as Finland, Iceland, and Norway, lie on the far left of the bell curve, standing at around 15 percent for C-sections despite women getting pregnant later, low birthrates, and increased obesity and health complications. The low rate of C-sections is due to having “strict guidelines about elective C-sections, cultural normalizing of vaginal birth, different legal attitude to medical litigation, and access to high-quality midwifery led care.”

In centuries past, it was commonplace to say Korean women gave birth in rice fields, not only because the time and date of birth were unpredictable, but also because hospitals were expensive and underdeveloped. However, this is no longer the case.

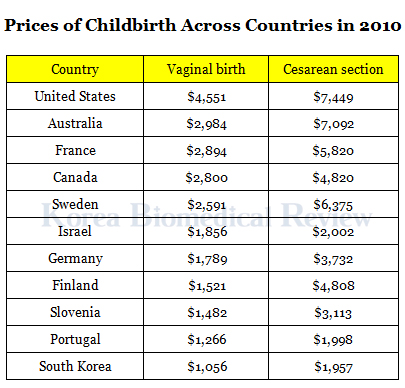

After the Korean healthcare system was unified under a national health insurance system, prices of hospital services rapidly decreased, and the prices of giving birth followed suit. The cost of C-sections in Korea is extraordinarily low, ranging anywhere from $1,000 to $2,000, while natural births hover around the $1,000 range. Other countries charge at least double Korea’s price.

Many gynecologists, who struggle to survive a low-profit OBGYN market, have traditionally resorted to C-sections since the surgical method is profitable and requires less patient care on the doctor’s part. Gynecologists who run their clinics have long complained of not making enough to keep their businesses going, with many opting out of providing childbirth services to other services such as vaginoplasty.

“Vaginal birth, although requiring an extended period of attention and care, is covered by national health insurance, meaning it is affordable. This notwithstanding, doctors have pushed C-sections onto mothers because it rakes in more revenue and requires less care on the part of the physician,” says Dr. Park Jae-young, author of “Incomplete Miracle: light and shadow of the Korean healthcare system” to be published later this year.

The problem is compounded by a competitive and rapidly changing society where women are more career-driven and less focused on raising a family, and therefore having children later. Medically, this is not good news, as older women are statistically found to have more complications with childbirth for both the mother and child.

Culturally, Koreans are no strangers to surgeries, as many choose to go under the knife either for cosmetic or medical reasons. Some prospective mothers want the surgical method to set a date and time that is intended to bring good fortune and luck for their baby, according to traditional Korean beliefs that a person’s birth hour, date, month and year are the “four pillars” that determine his or her life.

Others wish to avoid the consequences of a vaginal delivery. During a vaginal delivery, skin and tissues around the vagina can tear and stretch, requiring stitches or lead to impaired urine or bowel functions. Women wishing to avoid this issue may elect for the surgical method. Others say they want to avoid labor pains.

Cultural and social factors aside, studies show women are three times more likely to die in a cesarean section than a vaginal birth due to blood clots, infections, and complications from anesthesia. Also, women who have had a surgical delivery are more likely to select it in later pregnancies, along with the doctor’s recommendation.

Research also shows that women who have had cesarean deliveries also have trouble breastfeeding, later on, a problem avoided with vaginal delivery.

Babies also face a similar risk. C-section babies may be at greater risk for having breathing problems such as asthma, according to Live Science. During vaginal deliveries, “muscles involved in the process are more likely to squeeze out fluid found in a newborn’s lungs” which makes the chance of babies suffering breathing problems at birth lower.

In light of these problems, the government, media, and doctors have pushed to control the rate of C-sections by ranking OBGYN clinics on C-section rates, raising awareness, and advocating naturally-induced births, respectively.

Despite efforts of internal controls, the social phenomenon of women getting pregnant at a later age continues, with more and more women unable to give birth naturally.

“Of course, I, along with my friends, all prefer vaginal delivery. However, many of my friends are around my age, and we have little choice,” Lee, the working mom in her 40s, added.

Doctors also cite social and legal repercussions of accidents that could occur with naturally induced births – one of the reasons why some are quick to switch over to the surgical method when the slightest mishap occurs.

“We had a case recently where a gynecologist was sentenced to eight months in prison for the death of a fetus in a naturally-induced labor. The courts blamed the doctor for not resorting to the C-section, which could happen to anyone,” said Kim Dong-seok, chairman of the Korean College of Ob&Gyn. “The government is trying to force responsibility onto doctors for factors out of their control, countering efforts to decrease the number of C-sections in the country.”

"Aside from the question of right and wrong, the country has an inadequate system to deal with medical accidents which provide disincentives for doctors to advocate natural birth. Along with women getting married later, I don’t see the number of cesareans falling anytime soon," he added.