Top-10 news of medical community in 2018

Choi’s election as KMA head put relationship with government into turbulence

The result of the polls to elect the 40th president of the Korean Medical Association was very shocking. The winner Choi Dae-zip had records of activities in ultra-right groups and used to call for stating anti-government struggles, especially in opposition to President Moon Jae-in’s healthcare policy, called the “Mooncare.” In a way, Choi’s election reflected the medical community’s antipathy against the Mooncare and its growing sense of crisis.

“I will save the healthcare sector even by stopping healthcare service if needed,” Choi said while campaigning. “I will set a firm objective and stage social struggles to attain it not with words but actions. Now that the medical community can never back down from here, we can’t help but break through this crisis through a fight.”

As the president-elect of KMA, Choi raised social stirs with his political actions by, for instance, playing down the inter-Korean summit and Panmunjeom Declaration as a “deception of the public.”

Since Choi took office, KMA has held three national rallies. Toward the year-end, the doctors’ group is confronting with the government by revealing a difference of views in reforming the evaluation system of health insurance. The Ministry of Health and Welfare is reluctant to accept KMA’s demand to raise doctors’ fees by 30 percent, chilling, once again, the relationship between the government and the medical community.

Protect doctors from violence

Fists, steel trays, hammers, knives and fire; these were some of the weapons used to attack doctors. There were no limits in tools and methods to wielding violence against physicians at emergency rooms. The violence at hospitals, which had mostly been hushed up, came to surface in July when a patient attacked an ER doctor at the emergency room of a hospital in Iksan, North Jeolla Province. The accident enraged the medical community, forcing it to hold a massive rally in front of the National Policy Agency calling for the strict law enforcement and systemic reform to root out violence inside medical institutions.

Even before the aftermath of the violent incident calmed down, a patient attacked a physician with a hammer in Gangneung, Gangwon Province, and a drunken college student wielded a steel stray against the doctor on duty at the emergency room of the Cha Hospital in Gumi, North Gyeongsang Province, injuring the physician. At the emergency room of Namwon Medical Center in South Jeolla Province, a patient even brandished a knife against medical workers. The series of violent incidents at medical institutions has finally made the National Assembly move. Under the revised Medical Law and Emergency Healthcare Law, people who attack emergency medical workers at emergency rooms will face up to 10 years of a prison term or fines between 10 million won ($8,944) and 100 million won. If such violence leads to grave injury or death, the attackers will stay for a minimum of three years or five years in jail, respectively. The Assembly also strengthened the punishment to prevent the perpetrators from asking for leniency or having their punishment eased under the pretext of drunkenness.

Medical community exploded at the arrest of doctors for misdiagnosis

On Oct. 24, the Suwon District Court’s Seongnam Branch handed down prison sentences to three doctors and put them under court custody, for failing to make a correct diagnosis of a child who visited the hospital for four times because of stomachache, and leading him to death.

The medical community was greatly incensed with the news, criticizing the court for making a ruling without duly considering the medical reality and specificity.

Korean Medical Association President Choi Dae-zip and other executives shaved their heads and staged a protest rally in front of the court, which was followed by Choi’s one-person protest at the Supreme Court, Cheong Wa Dae, National Assembly and KMA headquarters in Ichon-dong in Seoul.

A sense of crisis that they may face jail terms because of misdiagnosis put together about 7,000 doctors at the third protest rally on Nov. 11. The participants called for creating a safe healthcare environment, pointing out that if the arrests of misdiagnosing doctors continue, it would lead to the spread of passive treatment and avoidance of healthcare service harming the general public.

The pediatric physician who received a one-and-a-half-year prison term, and emergency medicine doctor and family medicine doctor who got the one-year term, respectively, at the lower court, were freed on parole on Nov. 9, 39 days after they were taken into court custody. The Suwon District Court will make sentences in February.

Medical community tainted by ghost surgeries. Is CCTV an answer?

The social stirs caused by a series of ghost surgeries were enough to break public faith in the medical community. In September, a doctor and a nurse in Busan were found to have a medical equipment salesperson conduct an operation, and manipulated treatment records after the patient fell brain-dead. At a women’s hospital in Ulsan, an assistant nurse was known to have carried out Caesarian operations and incontinence surgeries no fewer than 710 times, causing a big social stir.

Even more shocking, ghost surgeries had been widespread even at the National Medical Center, designated as the principal practicing hospital of the national public health graduate school, as pushed by the government.

The series of ghost surgery incidents has led to loud public calls for obligating the hospitals to install CCTVs at operation rooms. To root out proxy operations and ghost surgeries, civic groups and patient associations called for installing CCTVs at operation rooms, making public the lists of doctors resorting to ghost surgeries and canceling their licenses, and applying charges of fraud and injury to violators.

Gyeonggi Province, in particular, set up CCTVs at operation rooms in the Anseong Hospital newly built in March, and decided to spread it to other institutions in the province.

However, the medical community, while agreeing on the need to eradicate ghost surgeries, opposes the installation of CCTVs at operation rooms, confronting civic groups and others who demand it.

Medical community not immune from shock of ‘52-hour workweek’

The 52-hour workweek system that applied to the businesses with 300 employees or more from July 1 has affected much the medical and healthcare community, too, and especially hospitals.

Medical hygienic services were included in the businesses exempt from the mandatory 52-hour workweek. However, hospitals scratched its head how to deal with the provisions that require the labor-management agreement to benefit from the exemption clause and that employers should give a break for 11 working hours or more. Nor were medical residents free from complaints about the 52-hour workweek.

In the recent economic ministers’ meeting chaired by President Moon Jae-in, however, the chief executive said, “It is important for the government policymakers to implement new economic policies, such as minimum wage hikes and shortened working hours, in ways to seek public consensus by considering social acceptance and standpoints of various interested parties,” opening the way for fine-tuning the workweek system that will go into effect next year. The medical community is paying attention to the President’s remark, hoping it would give them some breathing rooms in actual implementation.

Public medical school finally approved

On April 11, the ruling Democratic Party of Korea’s policymaking committee and the Ministry of Health and Welfare announced the results of their discussion on the “Plan to establish a public medical (graduate) school.”

Under the decision, the public medical school will be built with the objective of the opening in 2022 or 2023 in Namwon, North Jeolla Province. It will start with 49 students, making use of the quota at the now-closed Seonam Medical College.

In September, Rep. Kim Tae-nyeon of DKP sponsored a bill entitled the “Act on the establishment and operation of a national public medical school.”

The proposed school will take the form of a graduate university according to the Higher Education Act. The school will pay all the expenses needed for study, ranging from admission fees, tuition, expenses for teaching materials and boarding expenses.

However, students who give up their studies or fail to fulfill mandatory duty for 10 years after graduation or acquiring doctor’s license will have to repay all the expenses, have their licenses revoked, and not be able to regain it for another 10 years.

It stipulated as principal practicing institutions the National Medical Center and other national hospitals, provincial medical centers and public healthcare agencies.

As the medical community is going all out to block the establishment of the public medical school by, for instance, activating a task force, however, the issue will likely become a hot potato in the industry, and the government’s intention to foster medical workforce to serve in the vulnerable areas will likely face a tough sailing ahead.

Reform of healthcare delivery system goes up in smoke

To dissolve the concentration in large hospitals and revitalize primary health care, the government, healthcare providers and consumers put their heads together for nearly two years but failed to improve healthcare delivery system only reaffirming the conflicts within the medical community.

In December last year, the Korean Medical Association made public its draft recommendation on improving healthcare delivery system only to trigger fierce opposition from the medical community. The then KMA leadership under the President Choo Moo-jin was criticized for pushing for the reforms of healthcare delivery system in hasty, reckless manners.

In particular, the KMA recommendation caused strong opposition from surgeons, as it proposed to limit hospital beds for reason of reestablishing optimal functions for different medical institutions. The hospital group strived for the final draft of the recommendation even by conceding in the issue of outpatient treatment, only to give up at the last moment faced with the medical community’s adamant adherence to the “short-term hospitalized patients.”

After all, the two-year-long discussion on improving healthcare delivery system has ended up with little outcome, despite the final-hour attempts to adopt a recommendation.

Greenlight for ‘Greenland International Medical Center’ jolts the nation

On Dec. 5, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province approved the establishment of Greenland International Medical Center for foreign tourists while prohibiting its use by Koreans. The provincial administration also restricted the hospital’s services to four departments -- plastic surgery, dermatology, internal medicine and family medicine.

The “conditional approval” put an end to the six-year-long controversy, started by China’s state real estate group, Greenland, to set up a for-profit hospital in Korea.

However, the first approval of the “first for-profit hospital in Korea” made the whole country agitated while triggering immediate resistance from the medical community. Korea Medical Association President Choi Dae-zip issued a statement, saying, “The opening of Greenland International Medical Center will adversely affect the domestic medical system while opening the way for commercializing healthcare service.” Choi also met with Governor Won Hee-ryong to convey his protest.

The “Labor, civic and social organization demanding the cancellation of for-profit hospital and suspension of privatizing healthcare service,” composed of dozens of healthcare civic group and labor union, also staged a rally in front of Chong Wa Dae on Dec. 10, and held a news conference calling for the resignation of Governor Won and immediate action by the Moon Jae-in administration.

Conscious of adverse public opinions, Minister of Health and Welfare Park Neung-hoo, said, “The government will sternly deal with illegal activities through careful monitoring.” However, the controversy will likely continue through 2019 whether the hospital will be able to open and run as intended, given the fierce resistance from various sectors.

‘Valsartan incident’ throws people into cancer phobia

In July, the carcinogen NDMA ((N-Nitrosodimethylamine) was detected in the valsartan, the material of anti-hypertension treatment supplied by China’s Zhejiang Huahai.

NDMA is the “2A-class’ substance, as categorized by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which can serve as a carcinogen for humans.

The Chinese company is a supplier of pharmaceutical materials to the U.S., Europe, Japan and Taiwan. The European Medicines Agency first confirmed the detection of NDMA, and several countries began to temporarily suspend the sales of medicinal products using the valsartan substance supplied by Zhejiang Huahai.

The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety also suspended their sale. While the number of suspended items stood at about 10 overseas, however, the Korean regulators put as many as 219 products from 82 companies on the ban list, causing criticism of unduly scaring the general public.

The valsartan controversy came to a virtual close only on Dec. 19, as the ministry concluded that “an additional possibility of cancer outbreak is very low,” as the result of analyzing patients who took valsartan-containing medicines.

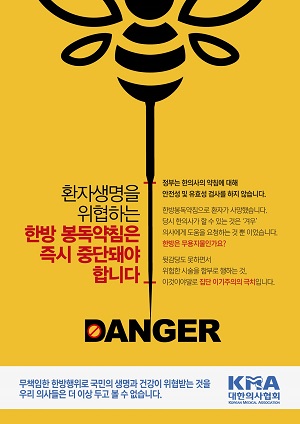

Doctor embroiled in a lawsuit for helping patient hit by bee acupuncture

On May 15, an elementary schoolteacher received bee acupuncture at an Oriental hospital in Bucheon, Gyeonggi Province. He died on June 6 after falling brain dead because of anaphylaxis shock. On the day of the bee sting therapy, the Oriental doctor asked for help from a family medicine physician in the same building as the patient’s condition aggravated. The Western doctor gave the first aid to the patient, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation until the 911 team arrived, but the patient died.

The Western doctor’s goodwill help came back to him in the form of a lawsuit. After the patient’s death, bereaved family members filed a civil suit demanding 900 million won ($805,000) in compensation, claiming he “failed to deal with the emergency properly.”

Faced with the news, the medical community strongly resisted, saying, “We must protect good Samaritans.” It also called for a complete exemption from responsibility as far as emergency care is concerned. Korean Medical Association President Choi Dae-zip declared war against Oriental doctors, vowing “never to intervene in adverse effects of Oriental medicine.”

The Oriental medical circles, on the other hand, embarrassed their Western counterparts further by pledging to use emergency medicines, including epinephrine, more actively. The association of Oriental doctors says there is no reason they cannot use it because there are no clear rules that prevent them from preparing and using such emergency drugs.

The bee string therapy controversy that stunned the medical community this year will likely continue through 2019, given the lawsuit between the bereaved family members and the Western doctor as well as the conflict between Western and Oriental medical circles over the use of epinephrine.