South Korea, infamous for having the highest suicide rate among OECD countries, faces another crisis as suicide rates among migrant workers continue to increase.

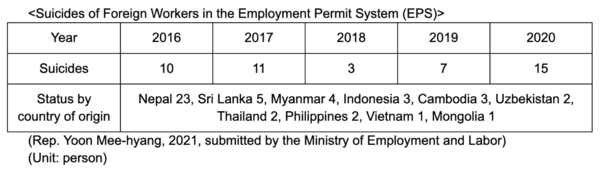

From 2016 to 2020, a total of 46 migrant workers in the Employment Permit System (EPS) died by suicide. According to statistics released by the Ministry of Justice, 15 workers took their own lives in 2020 alone, a 53 percent increase from 2019, while the ratio of migrant workers to the total population decreased from 4.87 percent in 2019 to 3.79 percent in 2021.

Suicide has been the second leading cause of death among migrant workers after traffic accidents, according to the Migrant Workers Mental Health Survey Report by WeFriends, an organization that promotes the health and well-being of migrants in Korea.

The 2022 study, “Depressive Symptoms Among Migrant Workers in South Korea Amid Covid-19 Pandemic,” by Shiva Achraya, states that 98.4 percent of migrants among a sample of 386 exhibited depressive symptoms.

Harrowing working conditions in Korea

The number of foreign residents in Korea was approximately 2.2 million as of October 2022, a report by the Korean Immigration Service showed. Out of those, 843,000 foreigners are employed, nearly 70 percent of which work in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with fewer than 30 employees.

Kim Mi-sun, the executive director of WeFriends, said that people often mistakenly believe that migrant workers develop mental health issues because they find it difficult to adapt to a new environment in Korea.

However, many immigrant workers say “It’s actually about work,” Kim said in an interview with Korea Biomedical Review.

“Everything in the workers’ lives is related to their workplace, especially if they left their family behind in their home country,” she went on to say.

“So if a problem arises at their workplaces, they can’t overcome it on their own.”

A factor that contributes to migrant workers’ stress about the workplace is the Employment Permit System (EPS), which makes it difficult for migrant workers to change workplaces even if they experience problems related to it. The EPS is a legal work visa system in Korea that provides migrant workers with three opportunities to move workplaces in the first three years directly after their arrival. However, if a worker changes workplaces more than three times or does so without obtaining employer consent, they become unregistered, which makes it difficult for them to find other work or send money back to their home country.

Furthermore, from this September, the government will limit foreign workers who entered the country on non-specialty work visas (E-9 visas) to change workplaces only within the region where they first started working to prevent the outflow of labor to other regions.

The jobs that the migrant workers take are nicknamed “3D”: difficult, dirty, and dangerous.

The Korea Institute for Health and Social Affair’s report on health inequality among migrant workers states that 29.8 percent of migrant workers have 60-hour work weeks, much longer than the standard 52-hour work week.

This is possible because workplaces with fewer than five employees or in rural areas are “blind spots” that are not subject to the Labor Standards Act.

This means that these workplaces are not required to abide by the 52-hour work week. In these places, migrant workers are not paid extra if they work overtime or during the weekends.

Furthermore, Lee, a 55-year-old Burmese counselor at a multicultural center in Korea and a Ph.D. candidate at Hanyang University for multicultural education, pointed out that employers often “don’t want to give migrant workers one day off to go to the hospital.”

“It doesn’t make sense that the Korean workers are allowed to take days off, but migrant workers have to continue working even when they’re sick,” she said.

Kim of WeFriends said migrant workers who wanted to return to their home country could not go back due to EPS-related issues.

“The most significant reason that the migrant workers take their own lives is definitely related to their work and the system that keeps them here,” she emphasized.

Social perception: discrimination and stigma

Another aspect of the poor mental health state of migrant workers is the way they are perceived by Korean society. According to the 2022 Human Rights Awareness Survey conducted by the National Human Rights Commission on 10,684 Korean citizens above the age of 18, 54 percent recognized that Korean society had hateful or discriminatory attitudes towards migrants. Furthermore, 58 percent of respondents stated that they would feel uncomfortable if a migrant worker became a lawmaker or the head of a local government in their region.

“Koreans expect migrant workers to assimilate to the Korean lifestyle and the Korean way of working, but they aren’t willing to learn about the migrant workers' culture,” Lee criticized. “Koreans know they can’t live without foreigners, but they fear that the foreigners are taking their jobs, property, and money.”

Plus, Koreans often treat migrant workers unfairly and disrespectfully in the workplace, so all of these factors work in combination and make it hard for migrants to endure, Kim said.

Indeed, according to the 2021 report “Research on the Existence of Racial Discrimination in Korean Society and Legislation to Eliminate Racial Discrimination” released by the National Human Rights Commission, 56 percent of migrants experienced “verbal degradation,” and 43.1 percent experienced “unpleasant stares.”

Kim also noted that migrant workers found it difficult to admit that they were experiencing problems with their mental health.

“Migrants fear the spreading of rumors, especially if they’re part of a community with people from their home country. If they show depressive symptoms, or can’t sleep or eat, they just think that it’s because they’re tired, and no one tells them to try counseling or get treatment,” which significantly worsens their conditions.

“They are not well educated,” Lee added. “Some of them don’t even know what counseling is.”

The impact of Covid-19

Although the entire country of Korea was affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, its migrant population was impacted disproportionately, especially concerning mental health.

At the beginning of the pandemic, migrant workers were unfairly blamed for the spread of Covid-19 and were excluded from early preventative measures such as the distribution of masks.

Additionally, the Seoul government issued an order forcing only foreign workers to be tested for Covid-19, only to rescind the order two days later after protests from the British embassy and others.

Migrants also had limited access to vaccine information. Korea only published vaccination guides in 12 languages while it received workers through the EPS from 16 other countries, whose languages were not all included. Meanwhile, Australia released information in 63 languages, and the U.S., in 65.

According to Statistics Korea, the unemployment rate for foreigners soared to 7.6 percent in May 2020 when the pandemic was raging across the nation.

Furthermore, the number of migrant workers who had unpaid wages increased from 23,885 in 2017 to 31,998 in 2020, according to reports released by the Ministry of Employment and Labor. Also, the amount of overdue wages increased from $61,726,398 in 2017 to $101,406,531 in 2020.

Social distancing measures forced migrant workers out of the workplace and into their homes, causing them to worry for their own and their families’ health, notably at a time when travel was restricted.

WeFriends reported that “this experience seemed to exacerbate already-existing depression or additionally cause insomnia and anxiety.”

Kim recalled that, when WeFriends conducted their first survey in 2020, the migrants from China, Nepal, and Myanmar had all lost their jobs and were living in temporary shelters. “So they were depressed and frustrated,” she remembered. “It affected their mental health, and that affected their physical health, so they had headaches and insomnia and even became alcoholics.”

However, the situation hadn’t improved at the time of the second survey, in 2022.

One of the defining emotions of the time of Covid-19 was fear, Kim recounted.

“They were afraid to be sick, but more afraid to die. They would always connect their death with their family, wondering who would take care of them when they died. That made the situation more severe for them and worsened depression.”

The future of migrant workers in Korea

The development of mental health problems among migrant workers laboring in Korea does not bode well for the country's future.

“We as a society still view migrant workers and refugees as people who will have to return to their home country one day, but that’s not what reality is like,” Kim pointed out. “Korea is already facing a population cliff, no children are being born, we lack a labor force, and our society is aging. However, we still don’t view migrants, refugees, and their children as part of our society, and this is especially clear in our policies.”

With plunging birth rates and rapid population aging, Korea needs migrant workers as a practical alternative to supplement a dwindling workforce.

According to Statistics Korea, the total population in Korea is expected to decrease from 51.84 million in 2020 to 50.19 million in 2040 as the birth rate dropped to a record 0.78 births per woman in 2022.

In particular, the number of Koreans of working age (15-64) is projected to decrease by 3.62 million over the next 10 years, from 35.83 million in 2020 to 32.21 million in 2030, and finally to 26.76 million in 2040.

These figures clearly show the lack of an economically active population in Korea.

On the other hand, since Covid-19, the number of foreign residents in Korea has been increasing. Among them, 80 percent are in the economically active age of 20 to 59. Therefore, the economic activity of foreigners in the domestic market continues to increase, which predicts an even greater reliance on migrant workers in the future.

What can be done?

WeFriends, as a part of their efforts to aid migrant workers, has established a Migrant Workers Suicide Prevention Project. Kim explained that they do the work of “connecting mental health centers and suicide prevention centers to foreigners, because they while they’re established, foreigners can’t easily access them.”

As word about the network spread, instances of migrant workers who attempt suicide were directed to WeFriends, which would then connect to hospitals and suicide prevention centers, providing migrant workers with therapy in addition to treatment.

Although this network, as well as the Migrant Workers Suicide Prevention Project, has seen success within the migrant community in the Northern Gyeonggi Province, Kim believes that “there needs to be more active intervention and interest from the government as well the embassies of migrant workers’ home countries.”

But that was not enough, Lee felt. More had to be done.

“Why doesn’t the Korean government hire people like me and educate people like me … so they can become professional therapists,” she asked.

“If you go to the multicultural center, there are therapists. But they aren’t foreigners. There’s a reason that foreigners don’t go to multicultural centers, because there’s no empathy. Koreans know the factory owners are wrong, but they only choose to see the Korean side.”

Furthermore, Lee felt strongly that “instead of educating the migrants, we have to educate the factory owners and managers,” believing that their awareness of mental health and foreign cultures will help them “understand the employees and what they need … If they know that the employees have a lot of stress because of culture or family, the owners can get help.”

“We came here, we are willing to learn, we are willing to earn money, we are willing to do whatever we can, but treat me like your own people,” she said. “Suicide can be prevented not only for the migrant workers but for the people of Korea.”