Three years have passed since Korea implemented the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision Act, but its decision criteria remain vague and insufficient to reflect patient wishes, according to a study.

A team of researchers at Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) analyzed cases of clinical ethics support services provided by the hospital's Institutional Review Board for three years after implementing the law and published it in the Journal of Korean Medical Science (JKMS).

Professor Yim Jae-joon of the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and Professor Yoo Shin-hye of the Center for Palliative Care and Clinical Ethics led the study.

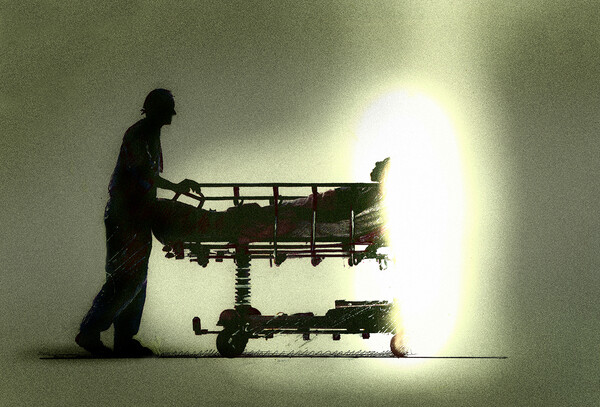

Medical institutions’ ethics committees are responsible for determining and implementing decisions to withhold or discontinue life-sustaining treatment. The clinical ethics support service helps medical professionals and patients make rational end-of-life care decisions.

Since the act's implementation, the SNUH Medical Institutional Ethics Committee has provided 60 clinical ethics support services from February 2018 to March 2021.

Some 56.1 percent of the patients were aged 60 or older. Those in their 70s accounted for the largest share, with 22.8 percent, with 17.5 percent being infants under 1. Of the total referrals, 47.4 percent were from the low-income bracket, and 21.1 percent were those on medical benefits.

Eight in every 10 referrals came from intensive care units. Cancer and cerebrovascular disease patients were the most common, with 25 percent each. Following their lead were those with respiratory diseases (11.7 percent), neurodegenerative diseases (8.3 percent, and cardiac diseases (8.3 percent).

Under the Life-sustaining Treatment Decision Act, only patients in the dying process can decide to withhold or suspend life-sustaining treatment. However, 66.7 percent of the patients referred to SNUH were not considered to be in the end-of-life process. They pointed out that the criterion itself of "no chance of recovery, no recovery from treatment, rapidly deteriorating symptoms, and imminent death" was vague and medically uncertain.

Ninety percent of patients had already lost decision-making capacity at the time of referral. Only 5 percent of patients could make decisions about their end-of-life care. Mostly, the patient’s children (36.7 percent), parents (35.0 percent), or spouses (28.3 percent) made decisions. In only 40 percent of the cases, the end-of-life plan reflected the patient's preferences or values.

Besides, only 26.7 percent of patients had expressed their wishes for end-of-life care before the referral. Some 16.6 percent had completed an advance directive or “do not resuscitate” (DNR) agreement and 6.7 percent had verbally expressed their DNR wishes.

"Under the current law, the outcomes of ethics committee deliberations are only advisory," Professor Yim said. “It is necessary to overhaul the system so that professional members can make decisions through the committee for unrelated people who do not have a surrogate decision-maker."

Professor Yoo also said, “Although there is an end-of-life decision-making law, it is difficult to estimate patient value, and there is a lot of clinical uncertainty. Further consideration is needed to ensure the best interests of patients."