As many of the “sole regional maternity hospitals” close one after another, even university hospitals, which have treated high-risk mothers and emergency cases, are faltering.

Three out of four obstetricians at the university hospital are considering resigning. The obstetricians noted they've had to bear the brunt of poor delivery infrastructure, but now they can't take it anymore. ‘We need colleagues to work with,” they said.

These are the findings of the “Survey on on-call and Working Environment of Obstetrics and Gynecology in University Hospitals,” released by the Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the workshop entitled “Obstetrics Education and Medical Care, Finding a Way Out of the Crisis” at the Suwon Convention Center Thursday.

The survey, conducted from Sept. 3 to 11, involved 111 obstetricians working full-time at a university hospital as of March 2024.

The average number of on-call days per month was 6.4 days. Forty-nine respondents (45.0 percent) reported being on call 11 or more times monthly. Worse yet, 26.6 percent were on-call 20 or more days per month, and 14 percent reported being “on-call throughout the month.”

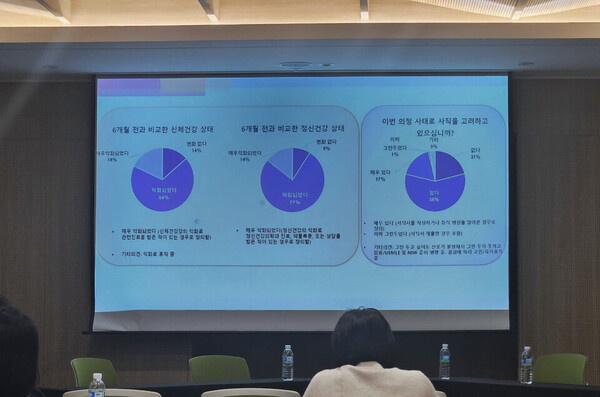

The overwhelming majority of obstetricians report that their physical and mental health has worsened since the outbreak. The deterioration in health has led them to see another doctor of a different specialty (18 percent) or seek mental health care or counseling (14 percent).

As a result, 75 percent have “considered leaving the profession amid the protracted medical turmoil. Of these, 17 percent had written a resignation letter or looked for a new hospital. In contrast, 21 percent said they had never considered leaving. “Even if I want to quit, I can't because I feel sorry for the mothers,” said one participant.

One percent said they had left or submitted their resignation since March.

The survey revealed a severe shortage of obstetric specialists at university hospitals. Some 20.7 percent of the surveyed said, “There was no medical staff available to work together in the event of an emergency, such as a delivery or surgery, while on call at night, meaning there are no professors, trainee doctors, and even nurses.

Accordingly, 73 percent of respondents said the most urgent need is to “increase the number of specialists to prepare for emergencies.” It was followed by increasing on-call fees (49.5 percent), ensuring rest after on-call (48.6 percent), and hiring more on-call doctors (48.6 percent).

Obstetricians said it's time to “choose and focus” to restore the delivery infrastructure, calling for establishing regional specialty organizations and introducing a “unified on-call system.”

“Rather than having obstetricians and NICUs at every hospital, it will be ideal to have regional specialty hospitals and bring professionals together so they can work together,” one obstetrician said.

Another respondent said, “I think it's unethical to accept patients when you don't have the resources. Instead, we should concentrate all high-risk patients in a few well-equipped hospitals to reduce accidents and the waste of resources.”

A third survey participant said, “We need to band together. We will never solve the ‘emergency room wandering’ problem if only a few obstetricians are in a university hospital.”

Related articles

- 30% of gynecologists over 60, with rural areas facing critical shortages in Korea

- Nearly 30% of Korean regions have no emergency care specialists: lawmaker

- ‘Collapse of childbirth infrastructure will accelerate unless government changes way of thinking’

- Government is recruiting trainee doctors despite the prolonged medical turmoil

- Korea still relies on manual jobs to provide nutrition therapy for preterm infants: experts