The golf ball vanished in midair.

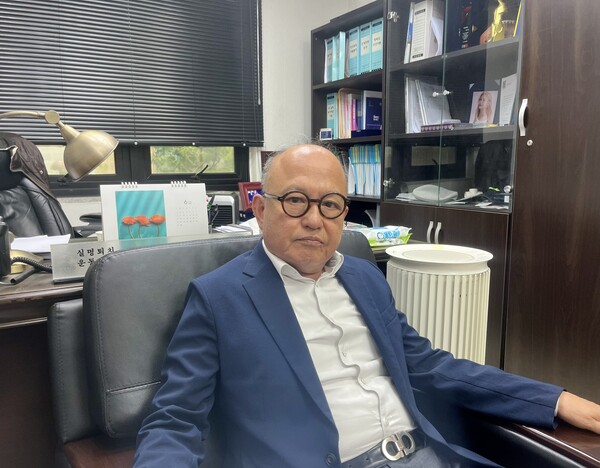

Choi Jeong-nam, who goes by Jonathan in English, blinked, swung again, and watched the next one disappear too. A week later, he scraped his sedan against a concrete pillar and stopped driving at night. That was 21 years ago.

At the time, Choi was 49, a Seoul National University–trained engineer turned fashion exporter, and still boasting 20/20 vision. He walked into Samsung Medical Center in June 2004 expecting a prescription, maybe a cataract referral.

Instead, the retinal specialist ran a series of tests, then told him: retinitis pigmentosa (RP), an inherited retinal dystrophy that causes progressive loss of sight and -- as the attending put it -- “has no treatment. You will go blind.”

Choi went home, opened his laptop, and typed “retinitis pigmentosa” into the search engine Naver. The results were sparse: a few blogs, a patient site with 500 members, and little else in Korean. So he switched to PubMed, FDA dockets, and translated what he found.

Somewhere in that search, he came across early reports from a Philadelphia startup called Spark Therapeutics. They were testing an adeno-associated virus shot targeting RPE65, a rare RP mutation.

That shot would later become Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec), a one-time gene therapy that delivers a working copy of the RPE65 gene into the retina -- now sold in Korea by Novartis.

Choi translated the research and posted summaries online under the pseudonym “Jonathan”. Within a year, the 500-member forum made him chairman. The group, now the Korean Foundation Fighting Blindness, represents what Choi estimates is “around 10,000 individuals, 20,000 if you include families.”

As the group grew, he organized benefit concerts led by his daughter, Choi Soo-young -- better known as a member of the K-pop group Girls’ Generation. Proceeds funded genetic tests for low-income families, and the band later became ambassadors for Korea’s blindness campaign.

Choi’s own mutation, CNGB1, tends to spare central vision until one’s 60s. Usually. “It’s unpredictable,” he said. At 71, he estimates he has “5 percent, maybe less” of his sight remaining.

During a two-hour interview with Korea Biomedical Review in a Gangnam office, he kept his eyes shut, not out of grief but because even ambient light caused pain. Shapes register as steam behind glass, he said. “There’s no meaningful difference anymore between night and day. What I see now is just a blur.”

Could he see me? “Just your outline. A shadow. If I squint, I can guess where your head is.” Color is gone, he said, and hair looks like a smudge.

He wears glasses for contrast, zooms in to read, but even that’s fading. His visual acuity is now below 0.1. “It’s like the last grains of sand slipping through an hourglass.”

When Korea Biomedical Review first interviewed him in April 2023, he had kept his eyes open. His central vision then hovered between 0.4 and 0.5, with glasses. Now, he opens them only briefly. If a future therapy works, the first thing he wants to see is his wife’s face. “Because a voice without a face is like a radio with static.”

A rare gene, an expensive cure, and a race against time

Luxturna was officially approved in Korea on Sept. 9, 2021, making RP a treatable disease, at least on paper. The treatment replaces broken RPE65 genes and, in global trials, restored partial sight in patients.

That same month, Samsung Medical Center performed Korea’s first subretinal injection in a woman in her twenties with Leber congenital amaurosis. She had gone blind as a child. After surgery, she could see outlines in the dark, edges of furniture, the world, again. “I never knew the world was so bright,” she said in a statement one month after the surgery. “I want to go to the cinema by myself -- somewhere I never dared go, even when I wanted to.”

But there’s a catch: RPE65 mutations account for fewer than 1 percent of RP cases worldwide. In Korea, they’re even rarer -- just 0.28 percent, based on unpublished 2022 sequencing data from 2,140 domestic patients.

As of Friday, only seven patients in Korea have received Luxturna, according to a note from Novartis Korea. The company declined to share treatment outcomes.

The health ministry began reimbursing Luxturna in February 2024 at a price of 650 million won -- about $235,000 -- for both eyes. Thanks to Korea’s copay cap, patients pay around 8 million won out of pocket. The procedure marked a milestone for Samsung Medical Center’s Center for Rare Diseases, designated as a national hub just months earlier.

“Even after a treatment is developed, cost can prevent it from reaching patients,” said Professor Kim Sang-jin, who performed Korea’s first Luxturna procedures, in a press release at the time. “We’re grateful that reimbursement allows us to continue this work, building on our first case of Leber congenital amaurosis three years ago.”

Still, money isn’t the only barrier. Diagnosis remains a bottleneck. Choi estimates genetic testing can identify about 70 percent of RP mutations, leaving 30 percent of patients in diagnostic limbo. “If the photoreceptors are gone, it won’t work,” he said of gene therapy. “You have to catch it early.”

Early usually means childhood. Unlike most RP patients, who go blind in their 40s or 50s, RPE65 cases often begin in kindergarten. Choi remembers struggling with night blindness as early as age six. “I remember moms and dads crying in front of me,” he said. “When their kids couldn’t see, doctors told them there was no treatment. So they just gave up. Enrolled them in blind schools. Moved on. No one followed up.”

That inertia lingers. “Even now,” a Novartis Korea spokesperson said, “there’s very little reliable information out there, making diagnosis very difficult.” Most physicians have little experience with these conditions, leading patients through a “trial-and-error” loop before reaching the right diagnosis.

The average IRD patient in Korea sees about eight doctors over five to seven years and is misdiagnosed two or three times, the company said.

Inherited retinal diseases are not a single condition but a spectrum linked to more than 300 genes, each with its own pattern of symptoms, severity and age of onset. Two patients may share a diagnosis but not a mutation, or access to the same treatment. “That’s why genetic testing is critical,” the Novartis spokesperson said. “Without it, there’s no way to even begin precision therapy.”

Lacking clear guidance, patients often reach for anything they can. “They feel lost,” the spokesperson said. “So they try vitamin A, lutein, anything someone says might help their eyes.”

Most physicians have never encountered an RPE65 case, leaving many patients untreated and unaware that a gene therapy exists.

Going blind, he built a biotech

By 2023, Choi founded Singularity Biotech with 300 million won scraped from fellow patients who "weren’t rich, but refused to wait." The eight-person team includes scientists and one nearly blind CEO working out of a fourth-floor office near Gangnam-gu Office Station. There’s no elevator. His driver takes his arm on the stairs.

The company's lead asset is a retinal progenitor cell therapy derived from human embryonic stem cells. These cells are extracted from retinal organoids -- lab-grown, retina-like spheres developed from pluripotent stem cells -- then injected into the eye to slow degeneration. Unlike gene therapy, which targets specific mutations, Choi said the organoid-derived cells work regardless of the genetic cause. They aim to stabilize photoreceptors and preserve vision.

Singularity’s cells do not depend on a specific mutation, and according to the company’s IR filings, manufacturing in Korea could bring the price closer to that of a cochlear implant.

Meanwhile, Korea's Samil Pharmaceutical announced a strategic investment on Tuesday, building on an earlier MOU to help bring Singularity’s tech through clinical trials and into the market.

Samsung Medical Center signed a separate MOU last month to help build a “living biobank,” using blood from RP patients to create induced pluripotent stem cells and then organoids that reflect their specific mutations.

Animal models, Choi says, don’t mirror human retinal disease. Organoids do. And unlike embryonic stem cells, they avoid ethical controversy. “One day,” Choi says, “I’ll have a milliliter of fluid that is my retina. We can test a thousand things before touching a real eye."

That vision tracks with new FDA policy. In April, U.S. regulators formally began reducing reliance on animal testing, encouraging lab-based organoid models for drug safety. Retina-on-a-chip systems might follow.

Studies suggest true total blindness affects only 1–2 percent of RP patients. Most can still detect light or motion. Early diagnosis helps catch secondary issues like cataracts or macular edema and determines eligibility for trials.

Korea’s first retinal implant surgery was performed in May 2017 at Asan Medical Center by Professor Yoon Young-hee. “Within 10 years, there may be multiple advanced regenerative options,” she told Korea Biomedical Review in a March 2023 interview. “Because RP is genetically diverse, a universal cure is difficult. But platform technologies may allow personalized solutions."

Choi believes the window is still open, though just barely. “The patients are out there. We just need to reach them in time," he said.

What will he look at first, if it works? He doesn’t hesitate. “My wife’s face. While she’s talking. That’s what I miss the most.”

Related articles

- Faced with 50,000 petitions, Assembly to debate increasing access to cell and gene therapy

- Rare retinal disease diagnosed using AI and prescribed with gene therapy

- 1st use of reimbursed Luxturna in Korea treats patient with inherited retinal degeneration

- Breakthrough soft artificial retina offers safe vision restoration for the visually impaired