“Initially, it was a disease deemed not worth researching because there was no treatment. However, I couldn't turn my back on the patients.”

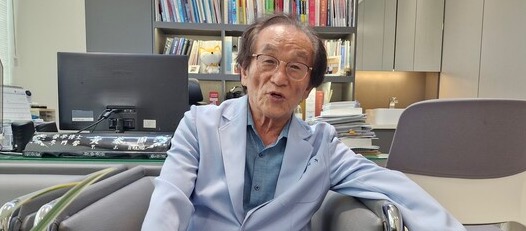

In the 1980s, a barren period for hemophilia treatment, one person boldly took a step onto that path. Dr. Hwang Tai-ju, who began as a professor of pediatric hematology and oncology at Chonnam National University Hospital, went on to serve as its president, dean of the graduate school, president of the Korean Pediatric Society, president of the Korean Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, chairman of the Korean Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, chairman of the Korea Hemophilia Foundation (2012–2021), and director of the Korea Hemophilia Foundation Gwangju Clinic. For nearly 50 years, he has stood by patients.

Shocked to see Japan already developing and treating hemophilia

Dr. Hwang's interest in hemophilia treatment began when he first encountered patients during his residency. Witnessing patients unable to use their legs properly or suffering disabilities due to bleeding made him realize someone must care for them. He was particularly shocked during his training in Japan, seeing that hemophilia treatments had already been developed and patients were receiving care.

“Our (Korean) patients often suffered disabilities from joint hemorrhages or lost their lives to cerebral hemorrhages, while Japan was using coagulation factor preparations extracted from plasma,” Dr. Hwang said. “Back then, there was almost no interest in hemophilia in Korea, and no treatments existed, so we had no choice but to rely on simple blood transfusions, plasma therapy, or cryoprecipitate transfusions.”

The catalyst for Dr. Hwang's full-fledged entry into hemophilia treatment was a proposal from former Severance Hospital Professor Kim Gil-young, whom he met at the Japanese Pediatric Society. Professor Kim, one of the few in Korea caring for hemophilia patients at the time, suggested to Dr. Hwang, who was contemplating the situation in Japan versus Korea, that they collaborate on patient care after Hwang returned to Korea. This led to the establishment of the Korea Hemophilia Rehabilitation Association in 1987.

The association collaborated with Korean doctors to provide patient care regionally and even held camps for patient education. They also visited the Ministry of Health and Welfare multiple times to explain the poor conditions faced by hemophilia patients, striving to expand welfare and secure treatments.

A turning point came in the late 1980s when GC Biopharma developed a Factor VIII treatment. “After GC Biopharma developed the treatment, the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Red Cross Blood Center implemented a patient registration program, supplying coagulation factor products free of charge to registered patients. This was later followed by national health insurance support, significantly improving patients' treatment environment.”

In 1991, the Korea Hemophilia Foundation was established, enabling more specialized and stable patient management and greatly improving patients' quality of life.

Hemophilia care: walking alongside patients, not just research subjects

Despite this, the treatment environment for patients with hemophilia remains limited. Due to the rarity of these diseases, patient numbers are low, and the high cost of treatments makes maintaining a consistent supply of medication a significant burden. As a result, even university hospitals often avoid treating patients with hemophilia. In Gwangju and South Jeolla Province, only Gwangju Clinic, affiliated with the Korea Hemophilia Foundation and Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, can accommodate patients.

“From the hospital's perspective, stockpiling expensive drugs is inevitably a burden. It's better to invest in other areas where the same costs can yield greater profits,” Hwang said. “If there are cuts, they have to absorb the losses, so they become reluctant to treat hemophilia patients.”

In the past, the lack of drugs actually fueled research motivation. However, most fundamental research on hemophilia has now been established, leaving few interesting topics. As a result, even university hospitals view it as an unattractive field, he pointed out.

Increasing patients’ average life expectancy from the 40s to the general population’s level

The lives of people with hemophilia today are vastly different from those of the past. Early patients had an average life expectancy of only the mid-40s, but it has now increased to a level nearly identical to the general population. This is largely due to the establishment of prophylactic clotting factor replacement therapy.

However, Dr. Hwang maintains a cautious stance regarding the introduction of new treatments. While existing treatments required intravenous injections, recent advancements include subcutaneous injections for greater convenience. Overseas, gene therapies are also being developed.

“The more experience we have with a drug, the more confidently we can use it. Primary care clinics lack the facilities to handle emergencies, making it difficult to use new drugs,” Dr. Hwang said. “Only when safety is sufficiently proven can primary care clinics utilize them.”

Dr. Hwang's caution toward new drugs stems not from reluctance, but from treating patients like family. Given that they must take medication for life, he believes it must be scrutinized meticulously, as if it were for his own family. Indeed, patients in Gwangju and South Jeolla Province were almost like family members for Dr. Hwang. For decades, he shared their lives not only in the clinic but also at small gatherings. He even visited patients with mobility issues personally to deliver treatment and medication.

‘May an environment be created where patients can become confident members of society’

Dr. Hwang emphasizes the need to support hemophilia patients beyond mere treatment, enabling them to live as confident members of society.

“While not entirely sufficient, patients can now live lives not vastly different from those of healthy individuals,” Dr. Hwang said. “I hope a social environment is established where hemophilia patients can possess self-esteem and forge their own futures.”

He also offered a stern reminder to future doctors.

"I was shocked by a news show yesterday. When elementary, middle, and high school students were asked why they wanted to go to medical school, some said they wanted to be like Schweitzer, but many answered, ‘because I can make money’ or ‘because it seems like a stable career for life.’ However, one must not view being a doctor as merely a job for making money. It's a demanding profession, but you must find fulfillment in treating patients with a sense of mission."

Related articles

- Hemlibra shows efficacy in bleeding prevention during exercise for hemophilia A

- Personalized prophylaxis becomes new standard in hemophilia treatment

- Sanofi's fitusiran earns orphan drug designation for hemophilia in Korea

- 'Separate treatment protocols needed for acquired and congenital hemophilia A'

- Hemlibra proves effective in improving hemophilia A patients’ joint pain

- New test enables patients using Hemlibra to assess their hemophilia severity

- GC MS launches Korea’s 1st domestically produced powdered hemodialysis agent

- GC Biopharma marks record-high sales of ₩609.5 bil. in Q3

- [Interview] Hemophilia care shifts from bleeding control to quality-of-life management