Saruparib, a next-generation PARP inhibitor in development by AstraZeneca, has garnered attention from cancer experts worldwide after showing clinical benefit in patients with homologous recombination repair-deficient (HRD) breast cancer.

However, it is questionable whether Korean patients who face significant restrictions on the use of first-generation PARP inhibitors will be able to benefit from next-generation drugs fully.

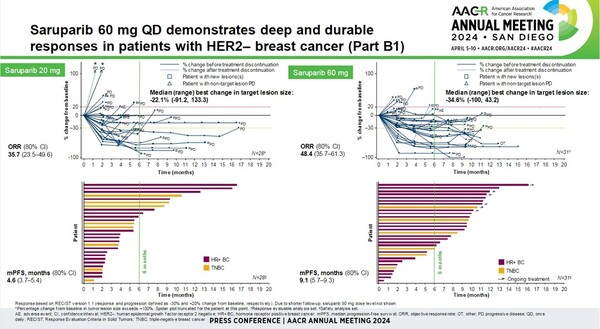

At the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting (AACR 2024) held in San Diego, Calif., on Monday (local time), the results of the phase 1/2 PETRA study of saruparib, a selective PARP1 inhibitor, were presented.

Its presenter, Professor Timothy A. Yap of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, highlighted the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) characteristics of saruparib and its potential for improved safety and efficacy over existing PARP inhibitors.

"Saruparib is the first potent, next-generation PARP inhibitor with high selectivity for PARP1," Professor Yap said, "It has a broader therapeutic index (TI), superior PK/PD characteristics and efficacy compared to previously approved PARP inhibitors, and can be conveniently administered as a daily dose."

Professor Yap explained that Saruparib's excellent safety profile and lower dose reduction rate compared to approved PARP inhibitors may improve efficacy by allowing patients to remain on the optimal dose for longer with superior drug exposure and maximized target activity.

"The majority of patients receiving saruparib 60 mg once daily achieved deep and sustained responses with high response rates and tumor reduction, and we observed prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) in a large cohort of previously treated breast cancer patients with a variety of HRR mutations," Yap added.

The PETRA study was a multicenter, phase 1/2 trial evaluating the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of saruparib in 306 patients with previously treated HRR-defective breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, including prior PARP inhibitors. Patients had one of the following HRR gene mutations: BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, RAD51C, or RAD51D.

Patients were treated with saruparib at doses ranging from 10 mg to 140 mg once daily, with 60 mg daily selected as the recommended dose for further clinical development.

Of the 31 breast cancer patients treated with supari 60 mg, the objective response rate (ORR) was 48.4 percent, the median duration of response (mDoR) was 7.3 months, and the median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 9.1 months.

Adverse events were observed in 92.2 percent of 141 patients receiving the 60 mg dose across all cancers, with 12.1 percent experiencing serious adverse events. Saruparib-related adverse events were observed in 76.6 percent of patients, with 2.1 percent experiencing serious adverse events related to the drug and 3.5 percent discontinuing treatment due to adverse events related to saruparib.

"The safety profile of saruparib was favorable, even when compared to the adverse event profile of other PARP inhibitors in phase 3 trials in treatment-naïve patients," Professor Yap said.

However, a professor at a major Korean hospital who heard about the results expressed excitement about saruparib but remained skeptical, citing restrictions on using existing first-generation PARP inhibitors in Korea.

"Even if a next-generation drug is developed, it will be difficult for Korean patients to receive timely treatment, considering even the first-generation drugs are not properly used here," the professor said.

In Korea, various PARP inhibitors, including olaparib (trade name Lynparza), niraparib (trade name Zejula), and talazoparib (trade name Talzenna), have been approved by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) for breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers, but only ovarian cancer gets insurance benefits.

Under the current system, an economic assessment should be conducted to expand coverage to other cancer types. However, it is difficult for pharmaceutical companies to prove cost-effectiveness and receive proper drug prices because the comparator drug is chemotherapy and for other reasons.

In particular, in the case of breast cancer, two drugs, Lynparza and Talzenna, are indicated, but neither AstraZeneca nor Pfizer have effectively given up on reimbursement for treating breast cancer.

Ingrid Mayer, vice president of global clinical strategy at AstraZeneca, also lamented the reimbursement reality of Lynparza, emphasizing the uniqueness shown in Korean patients with BRCA mutations.

"While in other countries, BRCA-mutated cancers are relatively rare and have fewer patients, South Korea has a high prevalence of BRCA mutations among breast cancer patients," Mayer noted.

That also explains why Korean patients play a key role in the clinical trials of AstraZeneca's next-generation PARP inhibitors, yet they cannot benefit from developed treatments.

Mayer added that while Korea's reputation for clinical trials includes an excellent infrastructure of clinical centers and medical staff, it also reflects the country's treatment environment, where patients have little access to new drugs outside of clinical trials.

In reality, AstraZeneca's ongoing PETRA study of saruparib includes a large number of Korean patients. However, Korean and foreign experts who know about the Korean situation presented grim prospects for saruparib in Korea, citing the example of Lynparza.